Terezin Ghetto

Terezin (german Theresienstadt) was built by the Austrian empire in late 1700s and is named after the Austrian princess, Maria Theresia. The town itself served as a garrison town and on the other side of the river Ohre a fortress was built. Between 1941 and 1944, the garrison town became a collection camp for Jews who were to be deported to extermination camps in Poland, mainly Auschwitz. First, only Jews from Czechoslovakia (Bohemia and Moravia) were interned in the town’s military barracks, but from 1942 the Nazis began to forcibly relocate the town’s residents to make room for Jews from the rest of Europe and Theresienstadt became isolated from the outside world.

Theresienstadt was first meant as a ghetto for old Jews but then became a ghetto for ”prominent” Jews. For example, it could be Jews who had fought for Germany in the First World War or culturally influential jews who made the Nazis keep them alive for the time being. One of these was Rabbi Dr. Leo Baeck from Berlin. The Nazis called him the Jewish pope and had his own apartment in Terezin. Other ordinary Jews found themselves living in overcrowded barracks.

When a new transport of Jews arrived in Terezin, they first had to go through something called Die Schleuse (canal). There the Jews were searched for things forbidden in the ghetto. Women and men were separated and housed in separate barracks named after German cities. Hannover and Hamburg for male Jews, Dresden and Magdeburg for female Jews. In ”Magdeburg” housed the office of the Jewish self-management (Jüdische Selbstverwaltung).

The first deportation eastward with Jews happened on January 9, 1942, when about 2,000 Jews were sent by train to Riga, Latvia. There they were murdered in Rumbula forest upon arrival. In September 1943, about 5,000 Jews were deported to the family camp in Auschwitz II – Birkenau. This was a section in Birkenau where they could move freely did not have to work. About 1100 of these died as a result of the conditions prevailing in the family camp. In 1944, the remaining were murdered in the gas chambers.

The ghetto in Terezin became in Nazi propaganda a pattern ghetto that would show the world that the rumors about Nazi concentration camps were false. The Nazis themselves never used the term pattern ghetto, but the official Nazi definition of the Terezin ghetto was Yudische Selbstverwaltung. Cultural events were allowed on in the ghetto but strictly monitored by the germans. A seven-team football league was also founded between 1942 and 1944, which played their matches in the inner courtyard of the Dresden barracks in front of cheering spectators. Nazis also gave permission to the Danish Red Cross to visit the ghetto in June 1944. This was a demand from the Danish government after about 500 Danish jews were deported to Theresienstadt in October 1943.

The inspection of the Red cross was by no means unheralded, but staged, and the Nazis had set the date and agenda for the visit. They made changes such as installing sinks and showers without connecting them to any real water pipes. Cafes were set up, playgrounds, music pavilions, theatres as well. In reality, life in Terezin was not much better than the ghettos in Poland. One might think that the Red Cross should have been more critical in their presentation of what they saw because in 1944 it was largely known what was going on in eastern Europe.

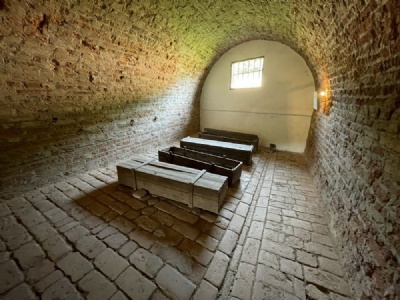

Due to maltreatment, starvation and lack of medicine thousands of prisoners died. Therefore, in October 1942 the Nazis built a crematorium with four ovens just outside the ghetto to cremate prisoners who died. About 30,000 prisoners from the ghetto, the small fortress and Litomerice camp were cremated. The Germans still allowed funerals for people who died in the ghetto. In parts of the fortress surrounding the ghetto, rooms were set up for funeral ceremonies and a columbarium where the ashes of the dead were kept in urns after cremation. In November 1944, the Germans decided that the ashes of about 22,000 people would be thrown into the river Ohre just north of the ghetto.

The Nazis also filmed a propganada movie to show the world Nazi camps and ghettos from thier point o view. The movie, filmed in August and September 1944, was also wrongly called Der Führer schenkt die juden ein stadt (Hitler gives the Jews a state), but its real title is, Theresienstadt – Ein Documentary film aus dem jüdischen Siedlungsgebiet (Theresienstadt – A documentary film about the Jewish relocation camp). The film was never shown because of the war. Of the film only 20 minutes remains. About 140,000 people were deported to Terezin during the war, of which about 87,000 were deported to Eastern Europe, mainly Auschwitz. The ghetto was not liberated until early May 1945, when commandant Karl Rahm handed over the ghetto to the Red Cross.

Current status: Preserved with museum (2000).

Location: 50° 30' 38" N, 14° 08' 58" E

Get there: Car.

Follow up in books: Gilberg, Martin: Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War (1987).

After the war, the Czech army took over several of the barracks that used to be the ghetto and remained there until 1997. Since then, the old garrison town has become a civil town with about 3000 people. However, the old ghetto remains and several buildings are now museums with interesting and modern exhibitions. Other buildings are abandoned or completely dilapidated, including the Dresden barracks where the football matches were played. All interesting places are within walking distance. The town lives partly because of its history and there are both hotels and smaller restaurants for visitors. The distance (about a kilometer) to the small fortress makes it possible to visit the ghetto and the prison in one day.