Le Vernet

North of the city Pamiers, Ariege, southern France, the French authorities established in 1918 a military camp for colonial troops that fought for France during the First World War. After the war, it became a prisoner of war camp for German and Austrian soldiers. After its closure the camp was used as a military storage area. In February 1939 the camp came into use again, now as a detention camp for about 15,000 Spanish soldiers from the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. In September of the same year it became a camp for ”unwanted” foreigners, anti-fascist intellectuals and members of the International brigade. In 1940, foreigners seen as national security risk were imprisoned. The camp was located in the free zone of France (Vichy) and in 1942 it also became a transit camp for Jews from the region. Between August 1942 and May 1944, five transports with a total of 859 Jews departed to Auschwitz via Drancy. In addition to Auschwitz, prisoners were also deported to Dachau, labor camps on the channel island of Alderney and Djelfa in Algeria. In June 1944, the last prisoners were deported by train to Dachau outside Munich. In total, between 30,000 – 40,000 people from 58 nations were imprisoned in Le Vernet. 215 people died in the camp and of these, 152 are buried in the camp cemetery. The Camp was demolished after the war.

Current status: Demolished with monument (2011).

Address: 2 Impasse Bruno Frei, 09700 Le Vernet.

Get there: Car.

Follow up in books: Weisberg, Richard H: Vichy Law and the Holocaust in France (1998).

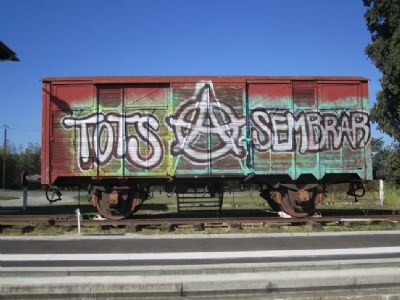

The Only remnants of the camp is a water tower and camp entrance poles. The station adjacent to the camp from which the Jews (and others) were deported also remains. In addition to the station, a prisoner freight wagon is on display, use to transport Jews. Inside the wagon is a commemorative plaque with the names of the 45 Jewish children between the ages of 2 – 17 who were deported september 1, 1942 to Auschwitz via Drancy.

The Holocaust in western Europe was a major logistical project, while in eastern Europe and especially the Soviet Union it was much less complicated. A round-up, for example, in southern France could begin with the Jews being held in a square or something similar. Here they could be kept for a shorter period befor being moved away. In many ways just like the Nazis did in Soviet Union. But in the Soviet Union, the Nazis took the Jews, who had not been selected for slave labor, to a nearby prepared execution site where they were shot. It could all be over in an hour.

In western and southern Europe, the Nazis had to deport the jews to eastern Europe before they were murdered. This was for several reasons, partly because Eastern Europe was completely under the control of the Nazis. Partly because it was more isolated than the west- and southern Europe. Partly because Eastern Europe was considered less culturally and developed than western Europe. And partly because the social ties between Jews and the rest of the population were weaker in eastern Europe than in the west. and souther Europe. In France, the majority of the transports with Jews bound for Eastern Europe departed from Drancy. But because France was so big, the Germans and their collaborators had to collect the Jews in assembly camps around France before they could be transported to Drancy.

This meant that the Jews assembled after round-ups in southern France were first taken to transit camps such as Le Vernet. There, they had to wait until the logistical and bureaucratic conditions had been arranged correctly. Not infrequently, transports were diverted to other places before they ended up in Drancy. It was not uncommon that they had to wait long times before they finally could be deported to Eastern Europe. With few exceptions, the transports went either to Auschwitz or to Sobibor, but some transports were diverted to, for example, the Baltic States. One reason for this could be a shortage of Jewish labor in these areas.

In the Baltic states (and the rest of eastern Europe) there were not many Jews left alive in 1943 and 1944, but at the same time the need for labor was huge. Therefore, local nazis responsible for the workforce were sometimes forced to turn to western Europe where the jews had not yet been murdered to the same extent as the eastern european jews. The deportations from all corners of Western Europe were in many cases a tremendously complicated process, due to the factual circumstances prevailing both locally and externally.