Topf und Söhne

In 1878, Johann Andreas Topf founded a company in Erfurt that manufactured waste ovens and cremation equipment. When Johann’s son Ludwig became more involved in the company, it was named J.A. Topf und Söhne. Under Ludwig’s management, the company grew internationally and from 1914 the company also came to manufacture cremation ovens. In the 1930s, it was Ludwig Topf’s sons, Ludwig and Ernst-Wolfgang, who ran the company. Both were well educated and became members of the Nazi party in April 1933, perhaps more for opportunistic reasons than for ideological convictions. When the military armament began in 1935, the company came to reverse the economic downturn the had suffered during the economic crisis at the beginning of the thirties.

By 1939, the company had about 1,150 employees. Until the outbreak of war, it was mainly silos that the company manufactured and sold, but also grenades and aircraft parts. In 1934, a cremation article was introduced in the German constitution with a number of paragraphs. One of these paragraphs stated that a cremation of a human being may only take place if the deceased’s relatives so wish and that the procedure should be worthy. It was further stated that only one person at a time may be cremated, the ashes must be collected, placed in a special urn with all information about the deceased’s full name, date of birth, place of birth, date of death, place of death, time of death and place of cremation.

At the beginning of the war Topf und Söhne was contacted by the SS. Topf und Söhne engineers with their expertise presented a solution for the disposal of dead bodies. In 1941, department D IV, led by engineer Kurt Prüfer, began to improve and develop furnaces for the incineration of waste, but also cremation furnaces for deceased people. They therefore began by designing and manufacturing cremation furnaces adapted to the needs of concentration camps. Buchenwald was the first concentration camp had needs for a cremation furnace. All because high mortality rate among prisoners during the winter of 1939/40. Topf und Söhne presented a solution in the form of a mobile cremation oven with double ovens that was actually designed to primarily cremate dead livestock and not human corpses.

SS was satisfied with this and got a mobile cremation furnace delivered to Buchenwald in the winter of 1939. Thus, the business cooperation between Topf und Söhne and SS was established and mobile cremation furnaces were installed in Dachau, Mauthausen, Gusen and Auschwitz. Later, when the number of dead prisoners rose, the camps ordered and installed stationary crematoria. These had a larger capacity than the smaller mobile ovens. But SS also collaborated with a small company that designed cremation furnaces, namely Heinrich Kori in Berlin. Kori had delivered cremation furnaces to the Nazi euthanasia program and later competed with Topf und Söhne to supply and install cremation furnaces in the concentration camps.

In November 1941, Topf und Söhne signed a contract from SS central building agency to deliver and install five triple ovens to Auschwitz and thus faced a new challenge. The SS central building agency was a division of SS Central economic administration (SS-WVHA) which, from February 1942, was responsible for the concentration camps, including their expansion. In Auschwitz, Karl Bischoff was the head of the construction projects. After Himmler visited Auschwitz in the summer of 1942 and decided that Auschwitz II – Birkenau would become a major extermination camp, Topf und Söhne was contracted to install two five-triple ovens in two large crematoria and two double quadruple ovens in two smaller crematoria to be built in Birkenau. The ovens were manufactured in Erfurt and disassembled via train to Auschwitz where they were assembled by technicians from Topf und Söhne.

Topf und Söhne also manufactured and installed the ventilation in the gas chambers as well as parts for the elevator that brought the corpses from the gas chambers to the crematorium on the ground floor. It was not only Topf und Söhne who were involved in the completion of the crematoriums. A total of 167 civil engineers and workers from seven companies were involved in the construction of the crematoria of Auschwitz II – Birkenau. Everything from technical equipment to mortar. Topf und Söhne also carried out maintenance, inspection and repair of its products. The SS helped several of the engineers and technicians to be drafted into the army. This because their expertise was considered more important than military service and repeatedly insisted on the importance of engineers like Karl Prüfer being present at the installations.

Kurt Prüfer himself was at Auschwitz a dozen times and testified after the war that he was well aware of what the concept of the Badehaus for spezial action (euphemism for the gas chambers and the crematorium) meant. According to Topf und Söhne, the capacity of the crematoria was 1440 corpses per day for the two major crematoria (II and III) and 768 corpses per day for the two smaller ones (IV and V). Another proof that Kurt Prüfer was engaged in practical solutions was that he tried to bring the heat from the waste furnace into crematorium 2 to the gas chamber. Zyklon B only works at a temperature of at least 25 degrees and Prüfer was keen to solve this practical problem. SS tried this but it did not work out the way they hoped. The gas chambers were nevertheless heated by the human body temperature. In 1943, Kurt Prüfer discussed with the SS the installation of a sixth major crematorium to meet the requirements of Auschwitz.

This was never realized because the Soviet Red army closed in on Auschwitz. Before the SS blew up the crematoriums in Birkenau, the ovens and other technical equipment had been removed to be installed elsewhere, for instance Mauthausen byt that never happened. In total, Topf und Söhne installed at least 25 single or multiple cremation ovens in four concentration- and extermination camps. The vast majority at Auschwitz. But the concentration camps never became the market that Topf und Söhne had hoped for and the total turnover of the company was no more than two percent. The competitor Kori installed at least 42 single cremation ovens in about twenty concentration camps.

Kurt Prüfer was arrested by the Soviet Union and sentenced to 25 years in prison, according to Soviet sources, he died of a heart attack in 1952. Ludwig Topf committed suicide in May 1945 before being arrested. Ernst-Wolfgang Topf escaped prosecution and started a new company in Wiesbaden, which went bankrupt in 1963. At the end of the fifties, he was confronted with information about his association with the SS and the concentration camps, but consistently denied that he had committed any crime. He felt that he did not know what the ovens would be used for. Ernst-Wolfgang Topf died in 1979.

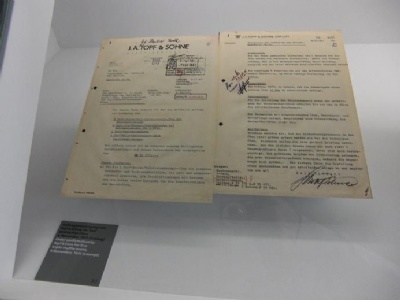

Topf und Söhne’s head office in Erfurt was located in the Soviet occupation zone and the company was nationalized and changed its production and could thus continue to exist without being held accountable for its activities during the war. The company later changed its name but no investigation of its history was ever conducted during the existence of East Germany. Only in connection with the dissolution of East Germany in 1990 an investigation about the company’s history began. After 1990 Topf und Söhne’s headquarters and facilities were becoming more and more dilapidated, but in 2003 the area was declared a historical heritage. On January 27, 2011, a museum was opened in Topf und Söhne administration building, focusing on the documents between Topf und Söhne and SS.

Current status: Partly preserved/demolished with museum (2011).

Address: Sorbenweg 7, 99099 Erfurt.

Get there: Car.

Follow up in books: Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials Foundation: The Engineers of the “Final Solution”, Topf & Sons – Builders of the Auschwitz Ovens (2005).

The challenges SS stood at Auschwitz went beyond their own technical expertise and therefore sought help from the civil sector. SS submitted offers and made procurements among companies about the services requested. Topf und Söhne’s collaboration with the SS is a clear example of how business cooperation between the SS (and Nazis in general) and the civil sector was much more common than one might think. It was simply a matter of a business deal between two parties where one offered a service and one paid for the services. No threats, just business. The companies and SS had regular correspondence with each other about general questions. Such as incorrect invoices, delayed payments, delayed deliveries, complaints, etc. For companies such as Topf und Söhne, the primary focus was to find solutions and improvements to the services and products that SS requested and paid for. Everything happened uncritically and without any moral scruples or ideological motives.

Most of the factory premises where the production and assembly of cremation furnaces took place don’t exist anymore. The museum is located in the former administration building and is quiet interesting. Its focus is on the link between SS and civil companies through a large number of displayed documents. The fact that the museum opened as late as in 2011 indicates that the cooperation between SS and the civil sector was a senestive topic, not really no how to handle it. This co-operation deviates from the traditional view of Nazism that has been characterized (and is characterized) by demonization where everything was done through threats and violence.