Thessaloniki

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Greece’s second largest city, Thessaloniki, had a Jewish population of about 50,000, representing about 70 percent of the total number of Jews in Greece. The majority of these were sephardic Jews who originated from Spain. Due to the high number of Jews living in the city it was sometimes referred to as Balkan’s Jerusalem. When Italy invaded Greece in late October 1940 it failed to defeat the greek army and Germany had to come to Italy’s rescue in April 1941. After Greece was defeated Greek mainland and the islands were divided between Germany and Italy. In this split up Thessaloniki came under German control. A small part of northern Greece was given to Bulgaria.

In the german part, anti-jewish actions was imposed immediately. Jewish leaders were arrested, Jewish assets confiscated, Jewish homes confiscated and Jewish hospitals were taken over by the germans and turned into military hospitals. Thessaloniki’s Jewish cemetery, probably the largest Jewish cemetery in Europe, was destroyed and the gravestones were used as building material.

In the summer of 1942, the Germans introduced anti-Jewish laws that restricted the legal, political and economic rights of the Jews. In July, 9,000 male Jews between the ages of 18 and 45 were ordered to appear in a large square in central Thessaloniki. In addition to being humiliated, about 5,000 were taken away as slave labor. In February 1943, the Jews were forced moving in to two open ghettos, one in the eastern part of the city and one near the railway station called Baron Hirsch. The latter later came to serve as a transit camp for the city’s Jews when the deportations began.

In December 1942, a special unit from the RSHA (Reich Central Security Agency) arrived in Thessaloniki to start the deportations of the city’s Jews. This mission was led by SS Hauptsturmführer Dieter Wisliceny and his colleague Alois Brunner. To their aid, the unit had the assistance of local military authorities.

As usual, the Nazis called the local Jewish leaders to a meeting where they were informed of the impending deportations. As elsewhere, they were promised that the Jews would be transferred to Eastern Europe and put to work. Local Jewish rabbi Zvi Koretz chose to cooperate with the Germans because he believed that the promises and explanations of the germans were true. Through active cooperation, he believed that he could appease the Germans and minimize any suffering and punitive measures. Over the next few months, Koretz paved the way for the deportations.

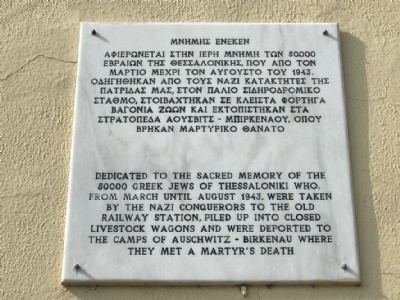

On March 15, 1943, the first deportation train departed from Thessaloniki railway station bound for Auschwitz. Deportations continued until August 1943, and a total of about 45,000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz, where most were murdered upon arrival in the camp’s gas chambers. The majority of the transports went to Auschwitz, but some went to Treblinka, Majdanek and Bergen-Belsen. Privileged Jews were deported to Bergen-Belsen, including Rabbi Zvi Koretz, and Jews with Spanish passports.

Almost all Jews from Thessaloniki were murdered in Auschwitz and there are several reasons for this. First, Thessaloniki was occupied by the Germans so any negotiations with foreign authorities were needed. The Jewish population was mainly concentrated in the central parts of the city. In addition, the Jews spoke a special ancient language called ladino and spoken by the sephardic Jews. This meant that they excelled linguistically and thus had difficulty hiding. But perhaps the biggest reason why the deportations were so successful was Zvi Koretz’s cooperation. The cooperation meant that administrative and logistical bottlenecks were rare.

Current status: Partly preserved/demolished with monument (2018).

Location: 40°38'29.83"N 22°55'29.14"E (old train station).

Get there: Bus or walk from central Thessaloniki.

Follow up in books: Gilberg, Martin: Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War (1987).

The sites in Thessaloniki are scattered over the city’s central parts but can be easily reached by bus or by walk. On the site of the Jewish cemetery is now the University of Thessaloniki. One might think how greek authority discussed when they decided to built a university on grounds of the former Jewish cemetery. Only in 2014 was a monument erected on the campus. At the new Jewish cemetery that was established shortly after the war is another monument.

The railway station where the Jews were deported has been replaced by a new one. The whole area seem to be semi-public and when I was there 2018, there were some seemingly self-appointed security guards who didn’t appreciate my visit. There is a memorial plaque on the station building and information boards next to the station. At the Freedom Square (Plateia Eleftherias) there is a monument. The square itself has been replaced with a large parking lot. As far as Iknow, there are no monuments or memorials in the two former ghettos.

As of this writing in 2018, there are plans to build a Holocaust museum in Thessaloniki. How far these plans as come when this is read, I do not know.